In 2017, historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage wrote, “The Confederate monuments in New Orleans; Charlottesville, Virginia; Durham, North Carolina, and elsewhere did not organically pop up like mushrooms. The installation of the 1,000-plus memorials across the US was the result of the orchestrated efforts of white Southerners and a few Northerners with clear political objectives: They tended to be erected at times when the South was fighting to resist political rights for black citizens. The preservation of these monuments has likewise reflected a clear political agenda.”

Brundage continues, “Few if any of the monuments went through any of the approval procedures that we now commonly apply to public art. Typically, groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which claimed to represent local community sentiment (whether they did or did not), funded, erected, and dedicated the monuments. As a consequence, contemporaries, especially African Americans, who objected to the erection of monuments had no realistic opportunity to voice their opposition. Most Confederate monuments were, in short, the result of private groups colonizing public space.”

There are roughly three times as many monuments honoring men of the Confederacy than monuments honoring heroes of the Revolutionary War. As Americans, we all benefit from our victory against the British, some more than others. But who, if anyone, benefits from the Confederacy’s loss to the Union? And why is the Confederacy, a failed attempt to split from the United States, still being celebrated with monuments, memorials, and much-beloved flag?

Below is an historical essay I wrote over five years ago. Before Charlottesville. Before Trump. In it you’ll be introduced to a handful of men who suffered through and survived the worst of the American Revolution and, subsequently, have been completely forgotten by their own country. They were POWs before POWs were ever defined. They suffered mortality rates that exceed the Korean War and Andersonville, both of which have been given memorials that are funded by the federal government. But there is no monument celebrating the Prison Ship Martyrs, those many thousands who lived and died, simply so that we could argue today about whether or not the statue of a Confederate general, an American traitor so intent on preserving the Southern state’s rights to enslave human beings for economic growth, could remain on display in a number of Southern states.

I used to believe that the Prison Ship Martyrs could never gain enough support from our government because the colonists were, by definition, traitors. They were rebels. They fought back against their own government. And they won. Why would the United States want to fund a monument that celebrates a rebellion against their own government?

Then it dawned on me: It’s much easier to appease the ones who lost, the Confedate States of America. This isn’t about people. This isn’t about democracy. This is about memorializing the loss. The government doesn’t want to honor the rebels who won.

***

In New York City’s East River sits a basin near northwest Brooklyn where human bones have regularly washed ashore for more than two centuries. The basin, referred to as Wallabout Bay, was once home to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, one of the country’s oldest naval installations. The Brooklyn Navy Yard began development in 1801 to support the newly established United States Navy, a military arm created by John Adams during his presidency. Over the years, the waterway’s natural channels were disrupted by construction and the river floor uncovered the horrors of war of which few Americans today are even aware. Even though the bones have been surfacing in cycles since 1795, nearly every new discovery has resulted in more failed attempts to honor the men and women who died in Wallabout Bay.

When construction of the Brooklyn Navy Yard began at the beginning of the nineteenth century, scores of human remains were uncovered by the dredging of the basin’s mud flats. In 1808, locals who knew the story behind the washed up remains again collected the bleached bones and skulls that littered the Brooklyn shoreline and placed them in a crypt to be buried nearby. Yet skeletal pieces continued to come ashore for decades, and personal accounts began to surface telling of the merchant seamen and privateers who had died on these waters. Their deaths were not the results of shipwrecks or maritime accidents, not of drowning or falling overboard. These deaths, estimated to be somewhere between 11,000 to 16,000 men and women, were instead the result of the unsanitary conditions and barbaric treatment inflicted upon prisoners held aboard British prison ships in Wallabout Bay during the American Revolution.

Between 1776 and 1783, at least sixteen prison ships, including the Jersey, Scorpion, and Good Hope, were moored in Wallabout Bay. The ships were employed by the British throughout the duration of the Revolutionary War. The British stationed prison ships up and down the eastern seaboard, some as far south as Charleston, South Carolina. The prison ships in Wallabout Bay, however, were notoriously brutal. Filth and disease were rampant aboard the vessels as prisoners suffered from diseases like smallpox, typhus, dysentery, and yellow fever. Prisoners’ poor diets often led to malnutrition from starvation or food poisoning, and contaminated water and dehydration were chronic concerns. More people died aboard these prison ships than in all the Revolutionary War battles combined. Held captive on these decaying hulks, the prisoners were mostly colonists, although some were simply unlucky foreign merchants.

The most notorious of all the prison ships was the HMS Jersey. Built during peacetime, the Jersey was a decommissioned fifty-four gun warship. The ship was nearly forty years old before she was stationed in Wallabout Bay as a floating prison. More than 1,000 prisoners were crammed together between decks at any given time. Poor ventilation and sanitation, on top of spreading diseases, led to approximately a dozen deaths each night. A familiar call every morning awakened the prisoners below: “Rebels! Bring up your dead!”

A number of first-person accounts were made public in the decades after the war. Andrew Sherburne’s Memoirs was written in 1828 and Thomas Andros published The Old Jersey Captive in 1833. The best known account, however, is Recollections of Life on the Prison Ship Jersey, written by Captain Thomas Dring. The manuscript was completed in 1824. Dring died in August of the following year, but it is noted that “his faculties were then perfect and unimpaired, and his memory remained clear and unclouded, even in regard to the most minute facts.” Dring, not yet a captain at the time of his unfortunate captures, was taken by the British in 1779 and imprisoned aboard the Good Hope. He managed to escape after a four-month confinement, but was again captured in 1782. He spent the next five months aboard the Jersey where he was “a witness and a partaker of the unspeakable sufferings of that wretched class of American prisoners, who were there taught the utmost extent of human misery.” The Jersey had a widely known reputation for death and wretchedness, and Dring and his comrades feared conditions on the ship before even stepping aboard.

The filthy environment aboard the aging ships promoted death and misery. In the case of the Jersey, its many gun ports were closed up and sealed off entirely. Ventilation and sunlight were nearly non-existent, leading to the areas between decks to carry a stench “so thick and putrid that it seemed to have tangible weight.” According to one prison ship survivor, Robert Sheffield, “The air was so foul at times, that a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which three boys were not missed until they had been dead three days.” Sheffield was captured in the summer of 1778 with nineteen other men. Three of them died within the first week. He referred to his prison ship as “a little epitome of hell.”

Food and water rations were poor, at best. Dring recalled the food allowances in his personal account explaining that one prisoner was responsible for collecting the rations each day for his mess, a designation given to one’s assigned group of fellow prisoners. Each mess received two-thirds that which was provided for those in the British Navy. One day’s rations usually consisted of one pound of biscuit, one pound of pork or two pounds of beef, a pint of oatmeal or peas, and occasionally butter, sweet oil, suet, or flour. The sweet oil was “so rank and putrid that we could not endure even the smell of it.” The bread was crawling with worms. Another survivor, Captain Alexander Coffin Jr., recalled “There were never provisions served out to the prisoners that would have been eatable by men that were not literally in a starving situation.” Coffin also noted having seen prisoners steal bran and slop from the troughs kept on board to feed the crews’ hogs.

The cook on the Jersey used the salty sea water from Wallabout Bay to prepare the prisoners’ meager rations in a giant copper boiler. “The copper became corroded and consequently poisonous,” Dring writes, “the fatal consequences of which must be obvious to everyone.” Coffin reported that the drinking water provided to him during his imprisonment was ordered and delivered by the city, but that “I never, after having followed the sea thirty years, had on board any ship, water so bad.” Another prisoner, Christopher Hawkins, claimed his drinking water came from the side of the ship “where all the filth and refuse were thrown.” Historians dispute this claim, however, as the water would be too salty, but historians agree it is entirely possible that this water, filled with filth and refuse, was probably used to boil and prepare the prisoners’ food. Historian John Ferling writes, “They tried to eat in this environment, too, cooking their food in a large kettle filled with water gathered from alongside the vessel, the very site where the previous day’s excrement was dumped each morning.”

Not surprisingly, disease was rampant. Lice, ticks, and other vermin flourished in the dark, dank bellies of the hulks. Typhus, dysentery, yellow fever, and smallpox were common and caused more than a dozen deaths each night, especially on the HMS Jersey. Many who managed to avoid or survive those diseases often “succumbed to the scurvy, which made their teeth fall out and caused their gums and eyes to bleed incessantly.” It was not uncommon to hear of prisoners who were so hungry or malnourished that they ate their own clothing. Sometimes they ate their own shoes. Rotten food and unclean water caused intestinal illnesses that resulted in tubs overflowing with human waste. Some survivors told of prison ships “whose decks were slippery with excrement.”

Historian Edwin Burrows describes the mortality rate of those held aboard the British prison ships by comparing them to events better known to the general public: The mortality rate among American soldiers who fought in the Korean War was approximately thirty-three percent; the mortality rate among Union soldiers in Andersonville, Georgia, was a bit higher, around thirty-five percent.

Andersonville was the notorious prisoner of war camp run by the Confederates during the American Civil War. Designed to hold 10,000 prisoners, Andersonville recorded a prisoner population of more than 32,000 only six months into operations. Food and water supplies were insufficient; medical care was nonexistent. Those who died had suffered from either disease, exposure, malnutrition, or a deadly combination of each. David Swain calls Andersonville “a humanitarian disaster,” adding that “incarceration in the Andersonville prison camp was probably as miserable but statistically less lethal” than life aboard the prison ship Jersey.

However, during the Revolution, when the entire American population hovered around only three million people, the mortality rate among prisoners held aboard the British prison ships was nearly forty percent. Some historians believe it is possible that as many as 16,000 died aboard the prison ships. If that is true, then mortality rates among prisoners could be as high as fifty percent.

Every person held aboard the prison ships was considered a traitor against the British. Since Britain had yet to acknowledge America’s independence, anyone charged with fighting for the colonists or aiding them in any way ran the risk of being imprisoned on board a ship festering with filth and disease in Wallabout Bay. The thousands who died aboard these floating prisons were often given another chance at freedom. By promising to enlist in the royal army or navy, a prisoner could buy his release with his newfound loyalty to the British. Most, however, chose not to, and instead faced certain death by remaining true to the American cause.

Those who died were buried haphazardly along the Brooklyn shoreline on the banks of the Wallabout. Prisoners looking for a means to leave the ship temporarily volunteered for burial duty. Dring writes, “The prisoners were always very anxious to be engaged in the duty of internment; not so much from a feeling of humanity, or from a wish of paying respect to the remains of the dead (for to these feelings they had almost become strangers), as from the desire of once more placing their feet upon the land, if but for a few minutes.” British guards were present as the prisoners on burial duty dug into the ground and heaved the bodies into a trench with little time to reflect. Dring recalled having been the only man in his detail to have worn shoes at the internment of one Mr. Carver. He removed his shoes at one point just to feel the earth against his feet.

In his memoir, Dring also wrote that he and a small group of other prisoners petitioned General Henry Clinton, then the commander of the British forces in New York, and requested to leave the ship in order to “transmit a memorial to General Washington, describing our deplorable situation, and requesting his interference on our behalf.” The petition was approved. The prisoners included information in written form, however the individual charged with delivering the message was also instructed to verbally inform General Washington of squalid living conditions and treatment being endured by the prisoners. Washington received the messages and shared his interest in working to mitigate their sufferings to the best of his ability. Unfortunately, there was little Washington could do directly.

The Continental Congress was repeatedly unable to improve conditions on board the prison ships, especially as they were unable to offer the exchange of British prisoners being held by the patriots. Even George Washington personally met with British officials in the hopes of keeping the situation from deteriorating, but to no avail. While the cruelty administered by the British encouraged colonists to continue fighting, those incarcerated aboard the ships were never considered prisoners of war. The treatment shown to them was more in line with the British exacting a sort of revenge against the colonists (and those who aided them) as traitors.

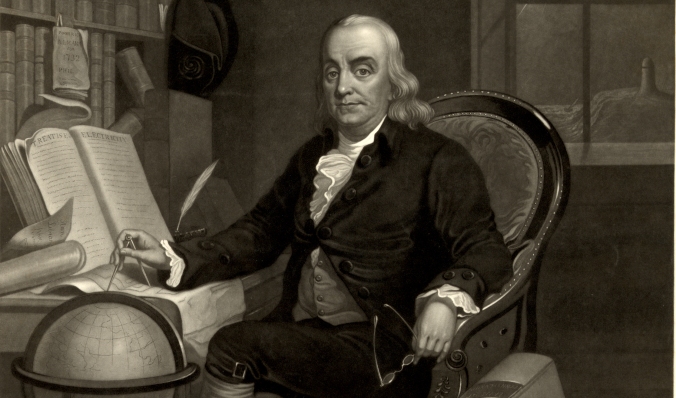

However, it was not until after the Revolutionary War had ended that Congress sent American diplomats Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams to negotiate such treaties with foreign powers. These treaties would ensure humane treatment of POWs in the event of future conflicts. The men and women who died aboard the British prison ships moored in Wallabout Bay became known as the Wallabout dead, or even the Jersey dead, regardless of their ship of imprisonment. The Jersey had been known to nearly all prisoners simply as “Hell” and represented the brutality inflicted upon those who lived and died. Later, the Wallabout dead came to be known simply as the Prison Ship Martyrs, a name still used today.

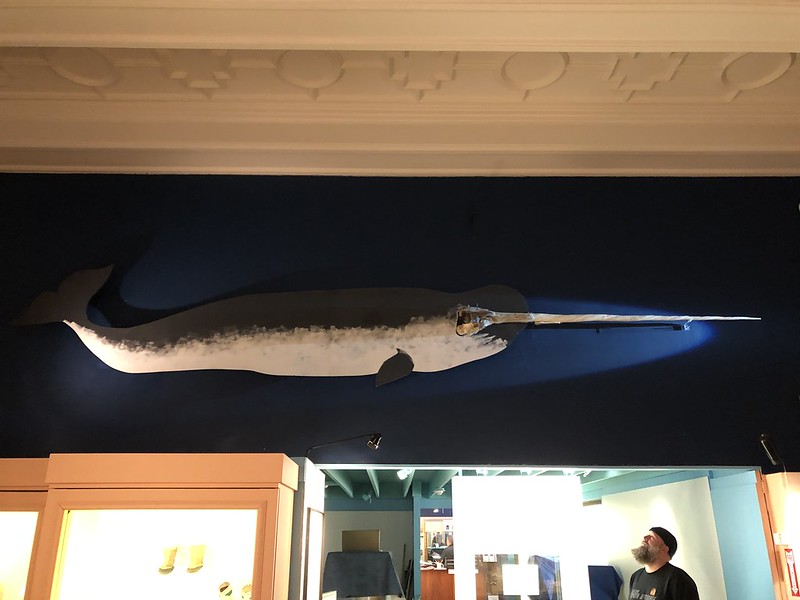

As remains continue to wash ashore over the following decades, the idea of a memorial has been proposed numerous times by locals, by influential community members, and by organizations who believe the Prison Ship Martyrs were an integral part of America’s victory in the War of Independence. While there is no denying the role the Prison Ship Martyrs played in the Revolution, there is also no denying that their story has been largely neglected in the pages of history. Yet another more widespread story of neglect continues to exist: There is no federally recognized memorial to the Prison Ship Martyrs.

(The monument pictured above is maintained by the New York City Parks Department and is funded entirely by private donations.)